With the increased use of CT scans, especially chest CT scans, more lung nodules are being diagnosed today.

When a lung nodule is found, many people become anxious and worry that it means lung cancer.

Of course, we know that this is not the case.

Lung nodules usually cause no symptoms. When a lung nodule is detected, the doctor will first assess it to determine its nature. The doctor will consider factors such as the likelihood of cancer and the appropriate course of action. They may decide to monitor the nodule with regular CT scans or order additional tests to better understand its nature. In some cases, surgical removal may be necessary.

What is a lung nodule?

A lung nodule is a shadow of increased density on imaging that is no larger than 30mm in size. They are usually symptom-free and are most often found incidentally during a physical examination.

A lung shadow exceeding 30mm is a lung mass, which poses a higher risk of cancer than nodules.

Depending on their density, lung nodules are classified as solid or sub-solid nodules. The latter can be further divided into pure ground-glass (no solid component) and partial-solid nodules (both ground-glass and solid components).

Lung nodules can have a variety of causes. They can be non-cancerous or cancerous. Most are non-cancerous, but a small percentage may be early-stage lung cancer.

An accurate diagnosis of lung nodules is needed so that, if there is a condition, it can be detected and treated early, or, if it is found to be insignificant or harmless, people can be spared worry and unnecessary intervention.

How is the size of a lung nodule assessed?

Although a larger lung nodule does not necessarily mean a higher risk of developing cancer, there is an association between the two. The larger the nodule, the higher the risk of developing cancer in general. The size of a lung nodule is therefore one of the factors used to assess its risk.

The size of a lung nodule is often expressed in terms of its diameter, which is usually taken as the maximal diameter or the average of the long and short diameters of the nodule.

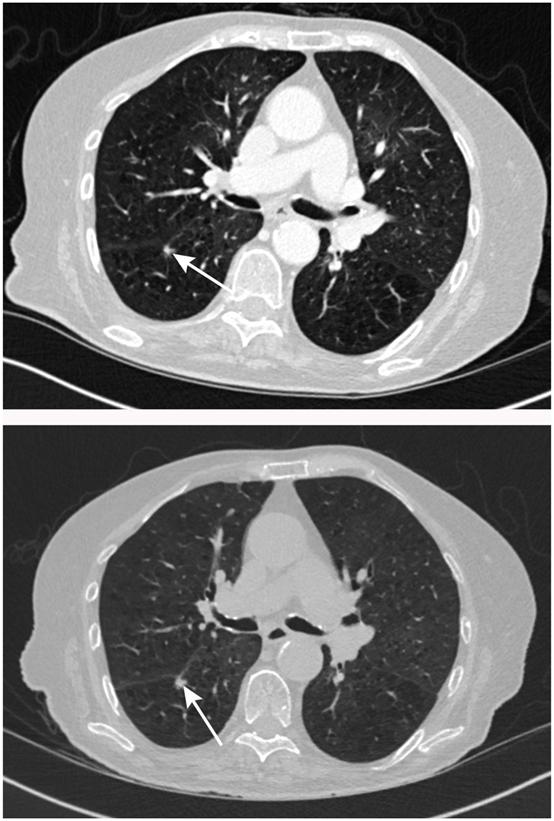

CT images showing the same nodule is larger than it was 5 months ago

Many lung nodules are irregular in shape and vary widely. Therefore, the resulting diameters of the nodules are only rough estimates and are often subject to some error.

And a small error in the measured diameter can lead to a large error in the volume.

The volume of a lung nodule is a more accurate indication of its size than its diameter.

In addition to size, the growth rate of a lung nodule is a more important factor in predicting its probability of cancer.

Growth rate can be expressed as an increase in diameter or, better still, as an increase in volume, the latter often expressed in terms of volume doubling time (VDT).

The radiologist can calculate the volume of the nodule on the computer and any significant (≥25%) increase in volume should be taken into account.

Assessment of lung nodules

Depending on the morphology of the nodule (solid or sub-solid), the British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines provide recommendations for assessment and treatment.

Risk models of assessment

Doctors use risk models to initially predict and calculate the cancer risk of lung nodules. Depending on their risk, decisions are made about further management, including regular follow-up, further tests, surgery, etc.

Risk models are based on the clinical features of the patient and the imaging features of the nodule. Different risk models have their own characteristics, with the Brock model and the Herder model both being commonly used.

The Brock model, also known as the PanCan model, has various parameters. These include the patient’s age, gender, family history of lung cancer, and the size, type, location, number, and morphology of the nodule.

Low-dose CT scans, which are commonly used for lung cancer screening, form the basis of the Brock model. As a result, it is particularly useful for predicting cancer risk in people whose lung nodules are found during a physical examination. In addition, this model has shown a higher detection rate for adenocarcinoma compared to other models.

For nodules larger than 8mm in diameter or 300mm³ in volume, the BTS guidance recommends the Brock model.

The Herder model is based on the Mayo model, using the same study methodology with the addition of parameters from PET-CT results. Its variables include the patient’s age, smoking history, history of extrathoracic cancer; size, location, burr sign of the nodule; and PET-CT findings.

The Herder model introduces PET-CT data as a parameter, which contributes to the assessment of cancerous nodules. This makes the Herder model suitable for use in populations with an increased risk of cancer.

Procedure for assessment of solid nodules

Solid nodules with clear features of non-cancerous diseases, or < 5mm in diameter (or < 80mm³ in volume), generally do not need follow-up or other management.

Those > 8mm in diameter and > 300mm³ in volume require assessment of the cancer risk using the Brock model. If the risk of cancer is ≥ 10%, a PET-CT scan with a further evaluation with the Herder model is recommended, followed by appropriate management and treatment.

When the size is between 5-8mm or 80-300mm3 in volume, follow-up CT scans are necessary to monitor the nodule.

Fig 1 Initial assessment of solid lung nodules

People with solid nodules ≥6mm in diameter or ≥80mm³ in volume will require a repeat CT scan after 3 months. If the Volume Doubling Time (VDT) is less than 400 days or if clear evidence of growth is found, further steps should be taken to clarify the nature of the nodule.

For people with solid nodules 5-6mm in diameter, a repeat CT scan 1 year later is usually recommended, followed by appropriate management and treatment depending on the change in nodule size or VDT.

If the nodule is stable on basis of volumetry, no follow-up is needed. And if it is stable on basis of diameter value, a review of CT scan after 2 years is recommended and CT monitoring can be discontinued if the result is stable.

Procedure for assessment of subsolid nodules

Sub-solid nodules < 5mm or stable for more than 4 years do not need management.

Otherwise, a thin-section CT scan of the chest is recommended once every 3 months to monitor changes in the nodule and assess its risk.

If the nodule is stable, it should be further assessed using the Brock model. The subsequent treatment should be based on the morphological changes in the nodule and the patient’s fitness and preference.

If the nodule grows or changes in morphology, surgical resection or non-surgical treatment would be considered.

Fig 3 Assessment of sub-solid nodules

Conclusion

This article outlines the process of assessment and management of lung nodules. This article is based on a guideline published in the British Medical Journal. The guideline is based on the British Thoracic Society (BTS) 2015 guideline and references the Fleischner Society’s 2017 guideline for the assessment of lung nodules.

However, it is important to note that the management of lung nodules needs to be implemented on a patient-by-patient basis. The guidelines should not be mechanically copied. Individual adaptations to the guidelines need to be made.

In addition, some tests are expensive and biopsies or procedures are invasive, so the pros and cons should be fully weighed. The options should also be discussed with the patient and his preferences need to be respected.